December 18, 2022

Today in Microsoft Flight Simulator, I’m flying the de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth, the airplane that trained thousands of pilots from across the British Empire to take to the air in World War II.

Born in 1882, Geoffrey de Havilland was the second son of a village pastor. At an early age, he displayed a mechanical interest and pursued a career as an automotive engineer, building cars and motorcycles.

Frustrated at work, in 1909 he received a gift of £1,000 from his grandfather to build his first airplane, just a few years after the Wright Brothers had made their first flight.

By World War I, de Havilland was working for Airco, where he designed a number of early warplanes (which enjoying varying success) and flew as his own test pilot.

In 1920, with the support of his former boss, de Havilland set up his own independent company, and embarked on a series of aircraft named after moths, inspired by his love of lepidopterology (the study of butterflies and moths).

In 1932, he introduced the DH.82 Tiger Moth, a variant of earlier moths designed specifically as a military trainer for the Royal Air Force (RAF), as well as other air forces.

Like many aircraft at the time, the Tiger Moth’s fuselage is constructed of fabric-covered steel tubing, while its wings are made of fabric-covered wooden frame. I’ve seen a single person lift a Tiger Moth by the tail to take it out of its hangar.

The Tiger Moth was powered by a de Havilland Gypsy air-cooled, four-cylinder inline engine which produced 120-130 horsepower, depending on the version.

Like most trainers, the Tiger Moth had two seats, each with its own set of controls, with the student in front and the instructor (or solo pilot) in back.

The silver knobs on the left control throttle, fuel mixture, and aileron trim. The knob on the right enables “auto slots”, slats on the wings that automatically deploy like flaps to provide additional lift at low speeds and high angles of attack.

Notice that there is no artificial horizon. However, there is a turn indicator (in the center) as well as a red column that indicates the aircraft’s pitch. It is currently showing nose-up because the plane is resting on its tailwheel on the ground.

The compass is a bit tricky. You can either keep it pointed towards north and look to where the line is pointing. Or you can rotate the compass ring to show current heading at the top and follow that heading by keeping it centered.

In addition to the cockpit gauge, there’s also a mechanical airspeed indicator on the left wing. Red shows typical stall speed range (below 45 mph).

One of the major changes introduced to the Tiger Moth, at RAF insistence, was folding door panels that made it easier to enter and exit both cockpits – absolutely essential when a student or instructor needed to quickly bail out with their heavy parachutes on.

I’m at Upavon Airfield, a few miles north of Stonehenge, which was home to the RAF’s Central Flying School, founded in 1912, and was where the first Tiger Moths were delivered. It is now a small army base (hence the vehicles) and is also used as a glider field.

With no electrical starter, the Tiger Moth is hand-propped to get it started. The turning of the propeller, by hand, engages the magnetos which in turn send charges to the spark plugs, starting the engine.

This particular Tiger Moth, N-6635, is based on the one currently on display at the Imperial War Museum at RAF Duxford, near Cambridge. It’s actually a composite that was put together with parts from different Tiger Moths.

The engine is modeled realistically. If you overstress it on full throttle for more than a few minutes, it will overheat and conk out. If you let it idle for too long, the spark plugs will foul up.

With a small engine like this, the left-turning tendencies are not pronounced. However, the trickiest part of takeoff for most tailwheel airplanes is still when the tail comes up. The descent of the rotating propeller causes a gyroscopic precession to the left.

The Tiger Moth gained immediate popularity as the RAF’s primary trainer – the first airplane a would-be pilot learned to fly, after ground school, before moving on to more advanced fighters or bombers.

It gained a reputation for being “easy to fly, but difficult to master”. In normal flight, it was forgiving of mistakes.

On the other hand, the Tiger Moth required great precision from a pilot to learn aerobatic combat maneuvers, without going into a spin. However, it recovers easily from spins, which meant it highlighted a student’s shortcomings without (usually) putting them at fatal risk.

I do notice that when flying upside down (or going through a roll), the engine sputters, probably because gravity messes with the fuel flow.

During the 1930s, between world wars, students selected by the RAF took about 9-12 months to earn their pilot wings, building up about 150 hours of flight time, about 55 with an instructor and the rest solo.

Their instruction included night, formation, and instrument flying, along with gunnery and aerobatics (for combat).

The Tiger Moth was sold to 25 air forces from different countries, and proved popular to private buyers as well. It was a big commercial success for the company.

A total of 1,424 Tiger Moths were produced prior to the outbreak of World War II, most of which were manufactured at the de Havilland factory in Hatfield, north of London.

By the way, notice what happens when I bank with the ailerons without using any rudder. The upper arrow (in the center) shows the turn is uncoordinated and the airplane is slipping sideways through the air. This creates drag and can contribute to a stall.

Now notice what happens when I apply some left rudder. The arrow pointer is now centered, showing that the tail is following the nose through the turn. Some aircraft are more sensitive than others when it comes to needing the rudder during turns.

I should explain that a “stall” has nothing to do with the engine conking out, like in a car. It’s when the airflow stops flowing smoothly over the wings and no longer produces lift, causing you to fall out of the sky. Luckily, if you’re high enough, you can recover.

There are no flaps in the Tiger Moth. So slowing down while descending to land can be difficult. I found I usually needed to cut the power to idle and glide in.

It’s nearly impossible to see forward in the Tiger Moth, especially when landing. It’s best to lean your head out the side, while keeping one eye on keeping the airspeed at around 60 mph (about 15-20 mph above stalling).

There are also no wheel brakes. So once you do land, you just have to let friction slow you down. It’s easier in a grassy field like this.

The success of the Tiger Moth led to Geoffrey de Havilland being awarded the CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1934. But its story was only just beginning.

Welcome to Goderich Airport (CYGD) in Ontario, Canada, about 2.5 hours north of Detroit on the eastern shore of Lake Huron.

In 1928, de Havilland set up a subsidiary in Canada to produce Tiger Moths to train Canadian airmen.

This Tiger Moth, #8922 (registration C-GCWT) is based on a real plane that belongs to the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum in Mount Hope, Ontario, and is in airworthy condition.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the British government realized that Britain itself was an unsuitable location for training large numbers of new pilots.

Not only is the weather often poor, the airspace over Britain was quickly becoming a battleground between the beleaguered RAF and the German Luftwaffe – the very last place you’d want a student pilot to learn how to fly.

Canada, in contrast, offered vast areas far from enemy activity, where pilot training could be conducted.

To take advantage of this, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was created, to train thousands of airmen from Britain and from across the Empire in safer locations like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Bermuda, and South Africa.

The yellow “training” livery was typical of the BCATP, though the real-life airplane was also equipped with a plexiglass enclosed cockpit to permit winter training.

Many of the small airports dotted across Canada from east to west – as well as some large ones – got their start as part of BCATP, commonly referred to as “the Plan”.

Here’s a nice zoom-in showing that external airspeed gauge on the wing strut in action.

I selected Goderich to fly from because after it was built in Canada in 1942, this plane, #8922, was used to train pilots here at the No.12 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS), as part of the BCATP.

Here’s a photo of the 14th class of pilots to graduate there in October 1941.

Here’s a photo of a student pilot standing next to a Tiger Moth at Goderich. Behind him, you can see what the plexiglass enclosed cockpit looked like.

The same airplane later went to No.4 EFTS at Windsor Mills, Quebec, an airfield that no longer exists. Eventually, there were 36 elementary flight schools across Canada, in addition to dozens more devoted to training bombardiers, navigators, and gunners.

131,533 Allied pilots and aircrew were trained in Canada under BCATP – the largest of any country participating in the Plan – of which 72,835 were Canadian. The program cost Canada $1.6 billion but employed 104,000 Canadians in airbases across the land.

De Havilland produced 1,548 Tiger Moths in Canada, by war’s end, to help stock these flight schools with aircraft.

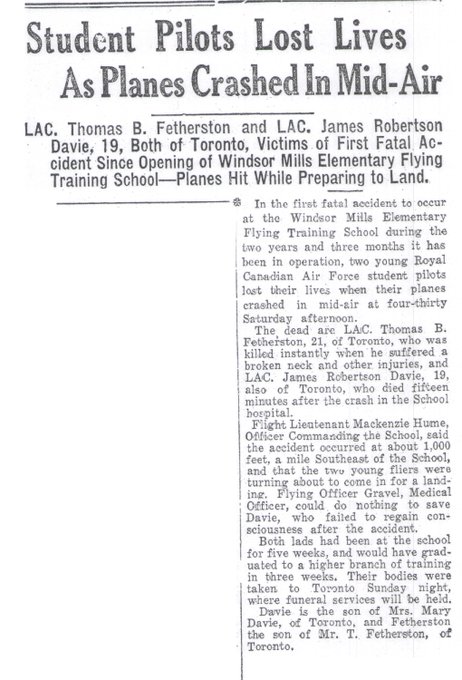

While training pilots in Canada was safer than in Britain, but lives were still lost. From 1942 to 1944, a total of 831 fatal accidents took place, an average of five per week. Here’s a newspaper clipping from Windsor Mills in September 1942:

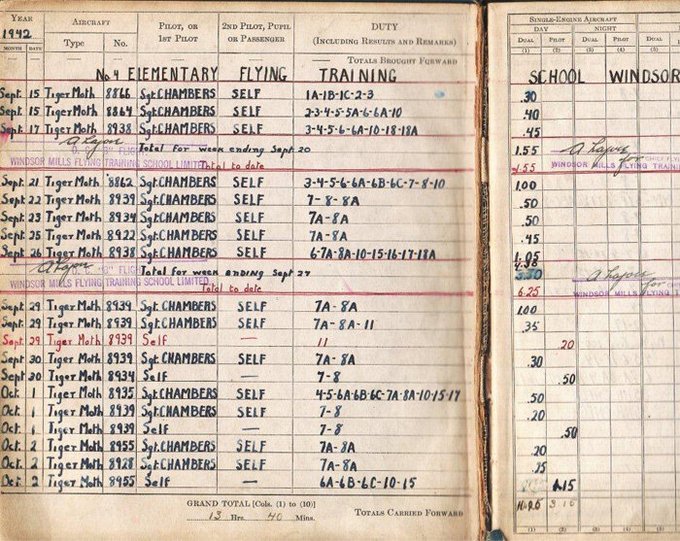

Here’s a page from the logbook of a pilot training in the Tiger Moth at No. 4 EFTS in Windsor Mills in 1942:

BCATP training was by no means limited to Canada. I’m here at Parafield Airport in Adelaide, Australia, which was home to that country’s No. 1 Elementary Flight Training School, which received its first Tiger Moths in April 1940.

This particular Tiger Moth, A17-58, was built by De Havilland in Australia in 1940, and apparently still continues to fly.

Australia eventually had 12 elementary flight schools (plus a host of other schools) as part of BCATP, which was known there as the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS).

Prior to BCATP, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) only trained about 50 pilots per year.

By 1945, more than 37,500 Australian aircrew had been trained in Australia, though many then went to Canada to complete their more advanced training before going into combat.

Most Australians in the RAAF went on to fight in the Pacific theater, though some joined the RAF to fight over Europe.

De Havilland built a total of 1,070 Tiger Moths in Australia, and even exported a few batches to the US Army Air Force and the Royal Indian Air Force.

The BCATP was one of the largest aviation training programs in history, and provided about half of the airmen who flew for Britain and its dependencies in World War II.

The program was so important that Franklin D. Roosevelt, who called the US “the arsenal of democracy”, dubbed Canada “the aerodrome of democracy” as a result of its contribution to training Allied airmen – many of them in the Tiger Moth.

Tiger Moths were not only used to train pilots during World War II. Some were used for coastal patrols. I’m here at Farnborough, Britain’s former center for experimental aircraft development (southwest of London), to investigate another interesting purpose they served.

No, it’s not a mistake. There’s a reason why there are no pilots in either cockpit. This aircraft, LF858, was what was known as a Queen Bee.

British anti-aircraft gun crews needed practice firing at real targets. But flying an airplane with people shooting at you is, well, rather dangerous.

So De Havilland figured out a way to put radio equipment in the rear cockpit that could receive messages for an operator on the ground and operate the aircraft’s controls accordingly. In other words, the world’s very first drone aircraft.

Besides being able to fly by remote control, the main difference between a regular Tiger Moth and a Queen Bee is that instead of metal tubing for the fuselage frame, the latter used wood (like for its wings) to save money.

The objective wasn’t to shoot the Tiger Moth down – that would be wasteful. Gunners used an offset to hopefully miss, so the airplane could land and be used again. But if they did hit, no pilots were at risk.

About 470 Tiger Moth “Queen Bees” were built during World War II. The term “drone” for a pilotless airplane derives directly from the Queen Bee program, and refers to a male bee who flies just once to mate with a queen, then dies.

By the end of World War II, nearly 8,700 Tiger Moths had been built, 4,200 of them for the RAF alone. It continued to be used by the RAF for training until it was replaced by the de Havilland Chipmunk in the 1950s.

The fact that so many people across the British Empire had learned to fly in a Tiger Moth made them immensely popular after the war, among private pilots and enthusiasts.

An estimated 250 Tiger Moths are still flying today, including this one based out of the small airstrip near Ranfurly, on the southern island of New Zealand.

A number of Tiger Moth clubs exist around the world, and at least one of you who replied to this thread said that they have flown one, in real life.

Christopher Reeve, of Superman fame, joined one of these clubs and learned how to fly the Tiger Moth. He even made a movie about it, which you can find on YouTube. He said it took some time getting used to how slow they approach and land.

Tiger Moths have appeared in several movies, often disguised as other biplanes. For instance, the plane in “Lawrence of Arabia” was a Tiger Moth, decked out to look like a German Fokker.

This airplane in “The English Patient” was a Tiger Moth. The other, yellow biplane in that movie was a Stearman. I’ll do a full-blown post on it sometime in the future.

I know someone will mention it, so I need to clarify: the biplane in “Out of Africa” was not a Tiger Moth, but the earlier and very similar Gypsy Moth, also built by de Havilland.

Apparently there was even a movie in 1974 called “The Sergeant and the Tiger Moth” about a guy and his girlfriend who aren’t even pilots but build and fly one anyway. I have no idea if it’s any good, so go watch it for me!

Regardless, I hope you enjoyed this thread on the historic de Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth, the first airplane that most British pilots in World War Il learned to fly, as well as the first pilotless drone.

[…] British-owned De Havilland company established a subsidiary in Canada in the 1930s, mainly to build Tiger Moths to train pilots from across the Empire at a safe distance from the front lines of World War […]

[…] stands for de Havilland Canada. In another post on the Tiger Moth, I mentioned how the British-owned de Havilland company established a Canadian subsidiary, starting […]

[…] You can see what that looks like, in contrast, flying in a Tiger Moth here: […]