December 14, 2022

Welcome back to Microsoft Flight Simulator where today I’ll be flying the Mitsubishi A6M2, Japan’s main fighter of World War II, famously known as the Zero.

Introduced in 1940, the A6M was dubbed the Navy Type 0 carrier fighter or Reisen (零戦, “Zero Fighter”) for short, in reference to the Imperial Year 2600.

To set the scene here, I’ll be taking off from the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi and flying over Midway Island, recreating the first wave attack in the Battle of Midway on June 4, 1942.

The paint scheme on this particular plane shows it belongs to a fighter squadron on the Akagi, as it would have looked during the attack on Pearl Harbor, and – very likely – during the Battle of Midway just six months later.

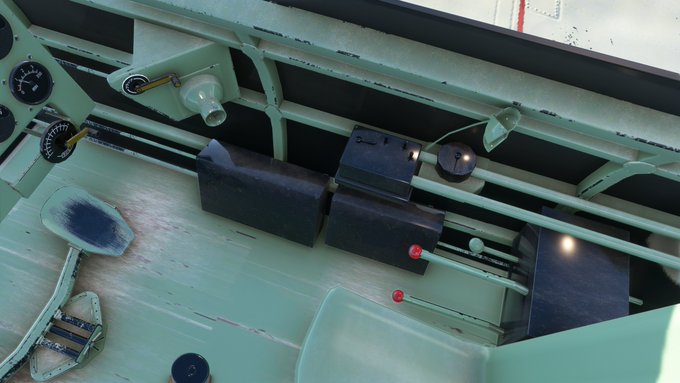

Inside the cockpit, the main instrument panel is topped by the breech and charging handles of twin 7.7mm machine guns that fire over the nose. I’m not sure what the characters, which seem to be numbers (736 and 245) signify. Would love to know.

To the right are the engine gauges. The top left is RPM, the bottom left is manifold pressure. (The Zero has an adjustable pitch, constant speed propeller).

To the left, from left to right, are the heading indicator, clock, and airspeed indicator on top, and the vertical speed indicator, magneto switch, and altimeter on the bottom.

To the left are the power controls. The black metal lever on the wooden throttle fires the plane’s guns. The two red-knob levers below them are bomb releases.

On the right side are levers for the flaps and landing gear, operated by hydraulics. Unlike the American F3F and F4F, the gear didn’t have to be cranked by hand, but the pilot did need to switch hands on the stick to operate them.

The cockpit is a tight fit, designed for smaller-stature Japanese pilots, who at this early stage of the war were extremely well trained.

Japanese aircraft carriers didn’t have catapults, so it’s just a straight run down the deck at max throttle to pick up enough speed.

The A6M Zero was designed in 1937 as a replacement for the A5M. Contrary to many movie portrayals, it was the A5M (aka Type 96) which participated Japan’s initial invasion of China. It also was an all-metal monoplane, but had fixed landing gear and an open cockpit.

When the design competition was announced, Japan’s Navy set such high standards for climb, speed, size, and range that the manufacturer Nakajima considered the task impossible and dropped out, leaving only Mitsubishi’s team.

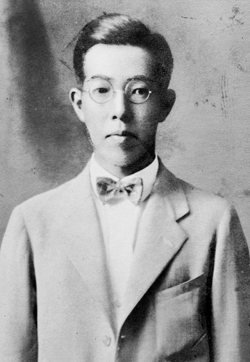

Mitsubishi’s lead aircraft designer, Jiro Horikoshi, believed it was possible to meet the demanding performance specifications and set out to prove it.

The key was to reduce weight to absolute minimum. To do this, the Zero was constructed from a top-secret aluminum alloy, which was very strong but very thin.

As a result, the Zero had a range of over 1,900 miles with a single drop tank, the longest range of any single-engine fighter of WW2, and ideal for a carrier-based strike plane. It also had an astounding climb rate and was extremely maneuverable.

This light-weight design also came with vulnerabilities: the Zero had no armor. In fact, that red square on its wings, above the flaps, is actually a no-stand zone, because the skin is so thin it can’t support the weight of a person.

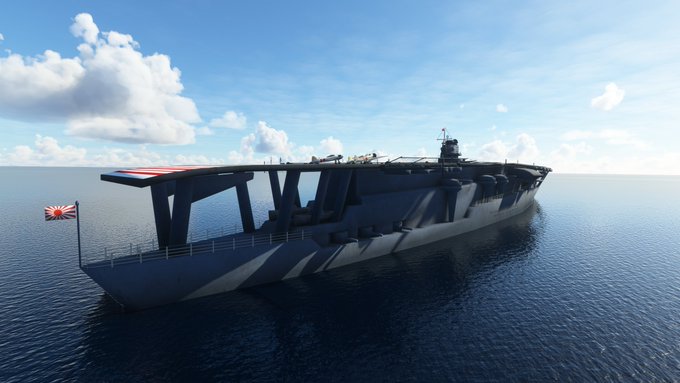

I’ll say more about the Zero in a second, but first, the Akagi below. Originally designed as a battlecruiser, after the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 it was converted to an aircraft carrier, with the help of Japan’s then naval allies, the British.

Akagi means “Red Castle” and is named after a mountain in Japan. Modernized in the 1930s, it could carry 66 airplanes including 18-21 Zero fighters. The decks are slanted to a peak to slow aircraft on landing and speed them on takeoff.

Nearby, I fly over the Kaga, the Akagi’s companion carrier at both Pearl Harbor and Midway.

The Kaga will be sunk by sundown, and my own carrier, the Akagi, will succumb to damage and slide beneath the waves the next morning. The attack fleet’s other two carriers, the Soryu and Hiryu, will also be sunk in this battle. But I get ahead of myself.

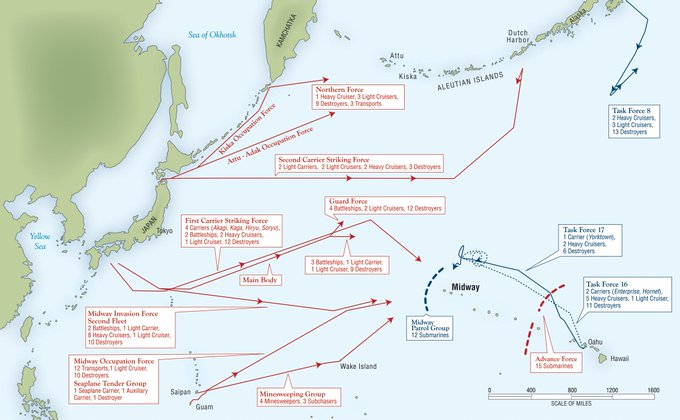

It’s time for me to head to Midway. The Japanese strike on Midway, in June 1942, was an attempt to lure the US carriers not destroyed at Pearl Harbor into a fight.

However, the US was able to decode Japanese messages that gave it prior warning of the plan, enabling it to position its three available carriers (Hornet, Enterprise, and Yorktown) for a surprise counterattack.

The Japanese opened with a carrier-based air attack on Midway itself, believing that any US aircraft carriers must still be far away. Time for me to drop my drop-tank.

Midway consists of two islands. The larger Sand Island, to the west, hosted a naval base, seaplane harbor, and fuel depot.

While the smaller East Island hosted an airfield with fighters and long-range bombers.

Making a strafing run at an unfortunate Liberty ship entering the harbor at Midway.

The Zero was armed with two 7.7mm (approx 30-cal) machine guns in the nose, plus two 20mm cannon in the wings. That was some pretty strong firepower, compared to comparable Allied fighters early in the war.

Now here’s an interesting tidbit: the Zero’s engine is basically a Pratt & Whitney copy. The Japanese had licenses to produce the DC-3, including engines, before the war, and reengineered it for the A6M.

It produced 950 horsepower, and was basically identical to the engine in the B-17. So much so that restored Zeros that fly today typically use the Pratt & Whitney engine, which fits perfectly.

In early dogfights with the Zero, Allied aircraft were completely outclassed. In China, it had a kill ratio of 12:1.

However, in July 1942 – a month after Midway – a Zero crashed in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands and was recovered and brought to San Diego for study, revealing some of the airplane’s hidden vulnerabilities.

For one thing, to save weight, the Zero eschewed the heavy rubber self-sealing fuel tanks that were becoming common in other fighters. This led to a tendency for it to catch fire and explode when hit.

For another, the large ailerons that made the Zero extremely maneuverable at low speeds made it harder to turn at high speeds, because of the airflow it had to deflect.

They also learned the Zero had a poorly designed carburetor which caused the engine to sputter in a dive.

All of these secrets helped the Americans design tactics to counter the Zero’s weaknesses (diving, high speeds turns, no armor) and deflect its strengths (climbing, low-speed maneuvers).

In another sense, the Zero was a victim of its own success. Because its designers had so creatively pushed it to its limits, there was little room for improvement in future models, to keep pace with new developments. It was as good as it would ever be.

While US aircraft – notably the P-38 Lightning, F6F Hellcat, and P-51 Mustang – either made or represented major improvements on previous designs, the Zero remained unchanged and continued in production through 1945.

The initial Japanese attack on Midway was largely successful, seriously damaging the US facilities on the two islands, and setting the oil depot ablaze.

However, it wasn’t enough. The raid leader reported back that a second wave would be needed to finish the job.

This news led to delays back at the Japanese carriers that made them easy prey for the surprise counter-attack that was coming from the US carriers quietly lurking nearby.

In any case, I’m ready to land back at the Akagi, not knowing what fate has in store.

The destruction of the Akagi and three other Japanese carriers dealt a severe blow to the Imperial Navy, mainly because of all the experienced pilots that were lost.

Coming in at around 70-80 knots to hit the arresting wires on the Akagi.

Even though it was outclassed by later US planes, the Zero could hold its own in a dogfight – so long as it was flown by a capable pilot.

The problem was, those pilots had been killed at Midway. By the end of the war, the Zero was relegated to serving as a flying bomb in the hands of relatively untrained pilots, as kamikazes on a one-way trip to take out US ships.

I almost forgot to mention one thing: what about the color scheme? The Zero I’m flying is painted a kind of greenish-cream color. Not for naval camouflage. It’s the color of the special coating used to protect the aluminum from corrosion, especially at sea.

Later in the war, camouflage from US air attacks became more important and many Zeros were painted green on top. The paint tending to flake off, though, and left the plane more vulnerable to corrosion. But that wasn’t their main priority anymore.

[…] Overall, the Wildcat and the Zero were fairly evenly matched, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. You might want to check out the separate post I did on the Zero here: […]