August 18, 2019

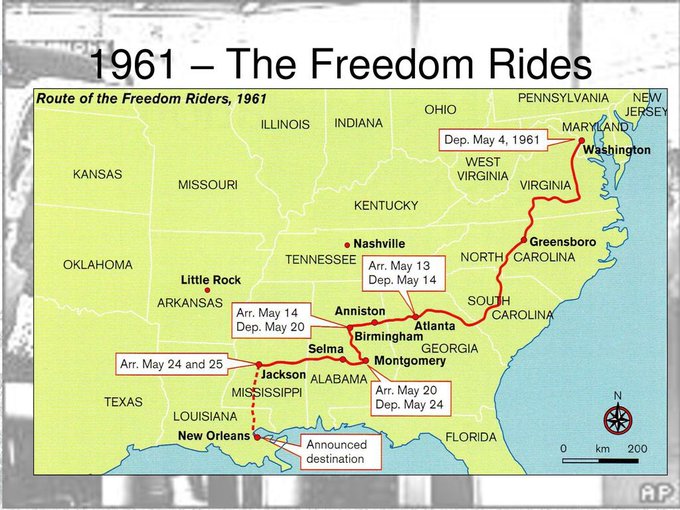

In May 1961, a group of interracial civil rights activists journeyed together through the South to challenge the non-enforcement of US Supreme Court rulings outlawing segregation on interstate buses. During a recent road trip through Alabama, I followed their path.

Dubbed the “Freedom Riders” and sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), they planned to travel a series of routes taking them from Washington DC to New Orleans.

For the first part of their trip, they only experienced relatively minor harassment. But as they departed Atlanta on May 14, Mother’s Day, they received warnings that a very different welcome awaited them in Alabama.

They traveled on two buses that day, one Greyhound and the other Trailways. En route to Birmingham, the Greyhound bus stopped at this terminal (left) in the small town of Anniston, Alabama.

The bus halted for boarding in this alleyway. The mural there today asks a haunting question: “Could you get on the bus?” (Anniston, Alabama)

A mob of local whites, many of them KKK, surrounded the bus and prevented it from moving. They slashed the tires and screamed at the passengers. The scene has hardly changed today.

Somehow the bus escaped the mob at the terminal, but it was followed, and a few miles down the road its slashed tires forced it to halt on the side of the old highway here, right where my rental car is parked.

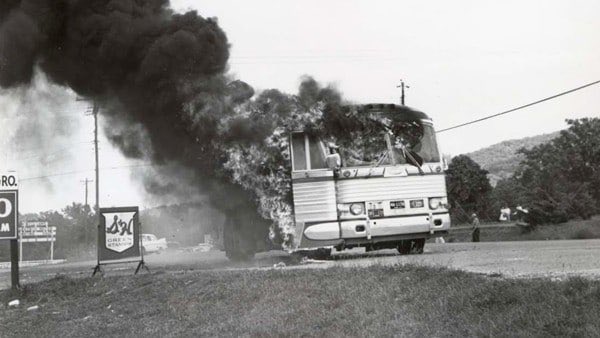

Someone smashed a window and tossed a firebomb into the bus. The passengers were trapped inside by the mob as the bus caught fire and filled with smoke.

Eventually they were able to claw their way out the bus door, where several were beaten by the mob gathered outside. No one died, but a terrifying message had been sent.

As I was viewing the site the other day, a man came out from his nearby house to take out the garbage. He greeted me and told me all about the day he had seen the bus burn.

Bernie Emerson was 31 that day. He had come from Wisconsin to work at the Anniston Army Depot. He ran outside and saw the bus burn right on the road outside his house, where he still lives. He often tells the story to people who stop to see the historical marker.

There are plans to build a more impressive memorial to the Freedom Riders outside Anniston, but so far they are still on the drawing board.

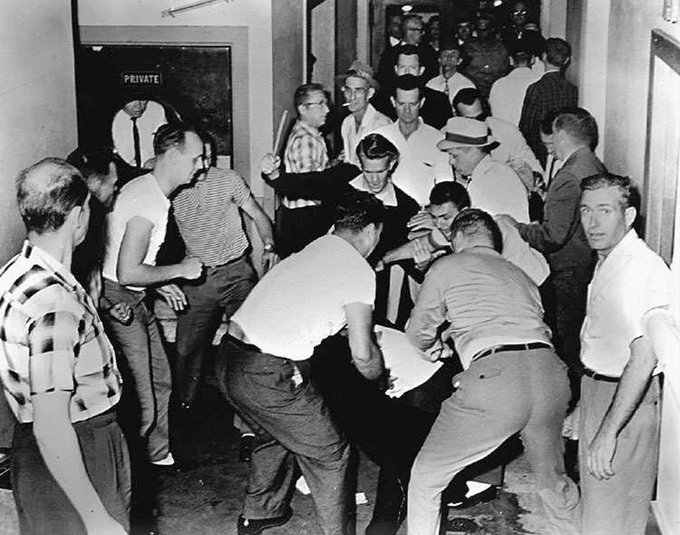

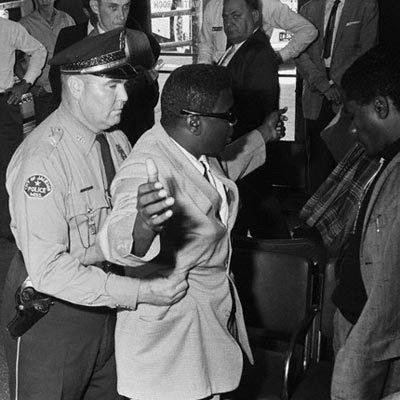

The other bus, the Trailways one, made it to Birmingham. Upon arrival at the bus terminal, they were beaten by a mob, with police nowhere to be seen. Here you’ll see they just noticed the photographer, who they proceeded to attack next.

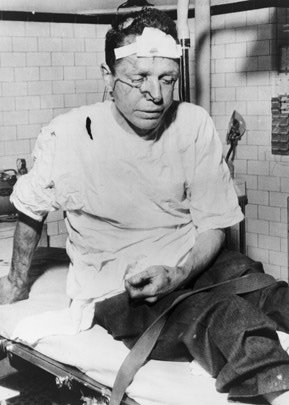

James Peck, the group of Freedom Riders’ team leader, was severely injured, but announced plans to continue their journey to Montgomery nonetheless.

The nation was shocked by news of the attacks in Anniston and Birmingham, and US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy sent a Justice Department emissary to Birmingham to persuade the Freedom Riders to quit, and to ensure their safe removal.

In the end, their determination didn’t matter: no bus driver was willing to leave Birmingham with them on board. Eventually they had to leave the city by plane, closely guarded by federal officials.

But in Nashville, CORE was planning to send new busloads of Freedom Riders to Birmingham to continue the trip, come what may.

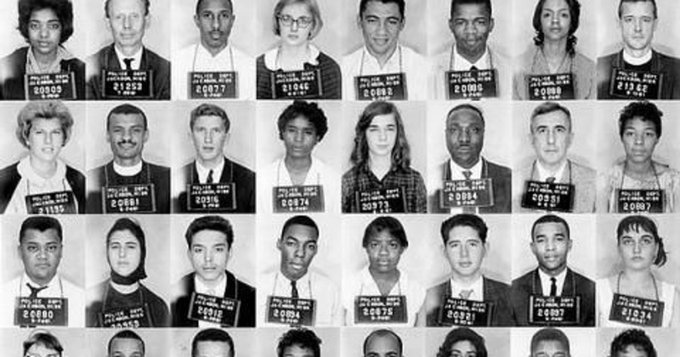

On arriving in Birmingham, they were arrested. Then they were released – but left unprotected. After frantic negotiations, Bobby Kennedy finally secured Governor John Patterson’s agreement to provide the Freedom Riders with state police protection through Alabama.

The Freedom Riders left Birmingham for Montgomery on May 20, 1961 with a huge police escort, including helicopters overhead, leaving them feeling safer – for the moment.

But as they entered Montgomery, the police escort disappeared. When they arrived at the state capital’s bus station – now a museum – another white mob was waiting.

White Freedom Rider Jim Zwerg, from Wisconsin, was the first off the bus. While the mob focused on beating him, several of his companions were able to escape.

Later that day, Jim Zwerg spoke of his determination for the Freedom Rides to continue from his hospital bed in Montgomery:

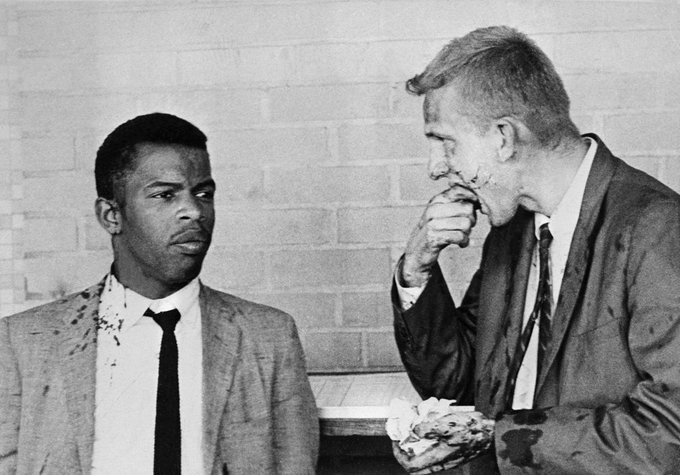

A bloodied Jim Zwerg immediately after the attack at the Montgomery bus station, next to a fellow Freedom Rider on that bus: John Lewis, later elected to Congress.

A US Justice Department official at the bus station, John Seigenthaler, was also attacked and beaten unconscious by the mob, prompting Bobby Kennedy to mobilize US marshals – which in many cases were just untrained local federal government employees.

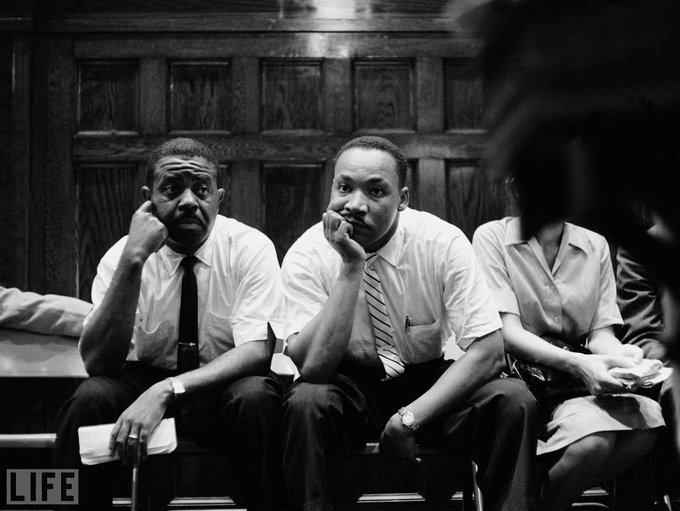

The next evening, 1500 people gathered in Montgomery’s First Baptist Church to hear top civil rights leaders, who had initially been skeptical of the Freedom Rides, including Martin Luther King Jr. welcome the riders in person and throw their support behind them.

Outside the church, however, a storm was brewing. A mob of angry whites had gathered and was rioting, and King and everyone else inside were trapped, with tear gas wafting in through broken windows.

Inside the church, Martin Luther King Jr. appealed for calm, in what was clearly a terrifying and dangerous situation.

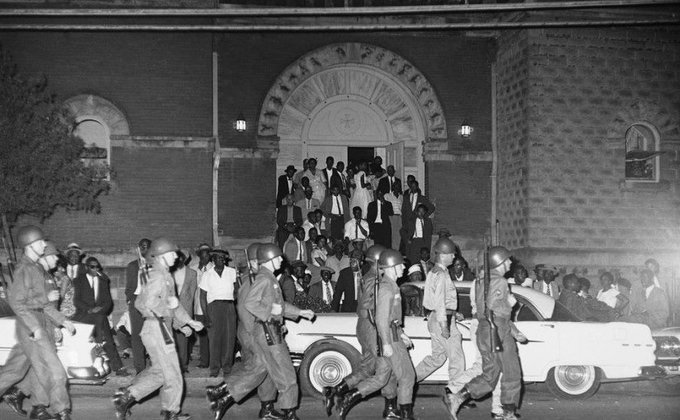

Finally, the Kennedy Administration persuaded Governor John Patterson to call in the Alabama National Guard to suppress the riots, putting the city under martial law.

The New York Times the following day, May 22, 1961:

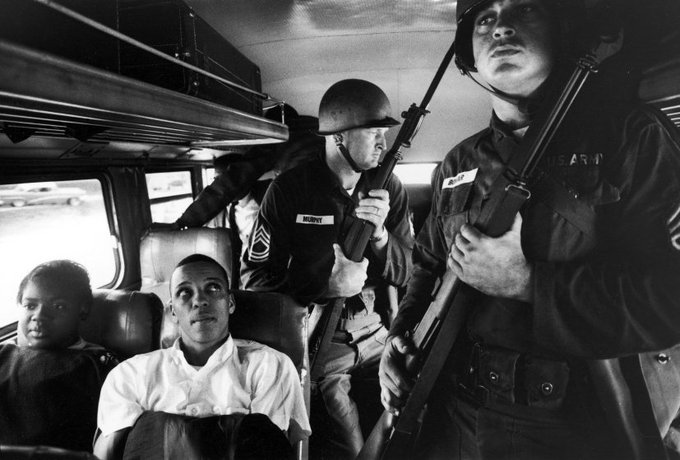

The Freedom Riders were allowed to continue, departing Montgomery bound for Jackson, Mississippi with an escort of armed Alabama National Guard soldiers aboard.

But once they reached the Mississippi border, they were handed over to that state’s National Guard and nobody knew what would happen.

In fact, when they arrived in Jackson, they were arrested and – as part of a deal with Bobby Kennedy – sentenced not to jail, but to the state’s maximum security prison in Parchman, Mississippi, which the governor figured would deter future riders.

Instead, CORE kept sending Freedom Riders into Mississippi, hundreds of them, determined to “fill the prisons” if that’s what it would take.

Eventually, the Kennedy Administration had the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) issue orders prohibiting racial segregation on all interstate bus routes. The order went into effect on November 1, 1961. The Freedom Riders had won.

It was a fascinating experience to follow the route of the Freedom Riders through Alabama last week, and visit some of the sites that defined their journey.

The lesson of travel is that history is real. These places exist, these things happened … and on occasion, you even get a chance to meet and talk to someone who saw it happen.

Mr. Emerson told me a story. He was at the barber shop in Anniston, getting a haircut. And some of the people there were saying “That never happened.” He told me, “You can’t argue with some people. But I know. I was there. I saw the bus burn.”

Leave a Reply