December 20, 2022

This is the Place!

There are about 77,000 wild horses, or mustangs, roaming the western US. To control their numbers, the Bureau of Land Management periodically rounds them up into corrals, like this one on the outskirts of Rock Springs.

Horses evolved in North America, spreading to Asia and Europe before going extinct here at the end of the Ice Age. So when they arrived back in America with the Spanish, and some of them broke free, they thrived in what was their natural environment.

We weren’t sure how close a view we’d get of them up on Pilot Butte, so we stopped by the BLM corral first to take some photos.

Then it was up to the top of the ridge on a windy gravel road to see what we could find.

The first thing that happened was three pronghorn antelope jumped out straight in front of our car. They were too fast for a photo, but we captured these two later.

It took a keen eye to spot them at first, as we were driving along. Can you see them?

We were about to give up on wild horses when we saw some brown shapes far in the distance.

Then as we drove along, we saw a couple of small herds of wild horses, grazing at Pilot Butte, Wyoming.

In the 1800s, people reported sighting huge herds of millions of wild mustangs, all across the American west. And of course, the reintroduction of horses to America fundamentally changed the way of life of Native Americans on the Plains.

For a long time, America’s wild horses were seen as a valuable resource. But after the invention of the automobile, they were seen as pests, competing with cattle and sheep for precious grass. They were hunted, rounded up, and turned into pet food.

When this became known, many people were quite upset, and in 1971 wild horses became legally protected. However, they thrive so well the herds keep outgrowing their sustainable population. BLM responds by rounding them up and putting them in corrals.

The view from atop Pilot Butte, looking south towards the Green River Valley and the canyonlands beyond.

The road down from Pilot Butte into Green River, Wyoming.

At Green River, we rejoin the path of the first transcontinental railroad, which left us at Guernsey, running south of the Migrant Trails.

Green River is where the one-armed Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell began his trip in 1869 to explore the Colorado River and into the Grand Canyon. Maybe this is his car.

Tall butte overlooking the town of Green River, Wyoming.

Rock formations near Green River, Wyoming.

The road north from Green River, Wyoming, to rejoin the Oregon Trail.

Some rather curious food items for sale at Little America, a rest stop in southwestern Wyoming.

We rejoin the Oregon Trail at Granger, Wyoming, site of a Pony Express station. In “Roughing It”, Mark Twain wrote about stopping here on a stagecoach, en route to Nevada.

Some distance southwest of Granger lay Fort Bridger, an important place for the Oregon Trail migrants – those that skipped the Sublette short cut, at least – to rest and regroup.

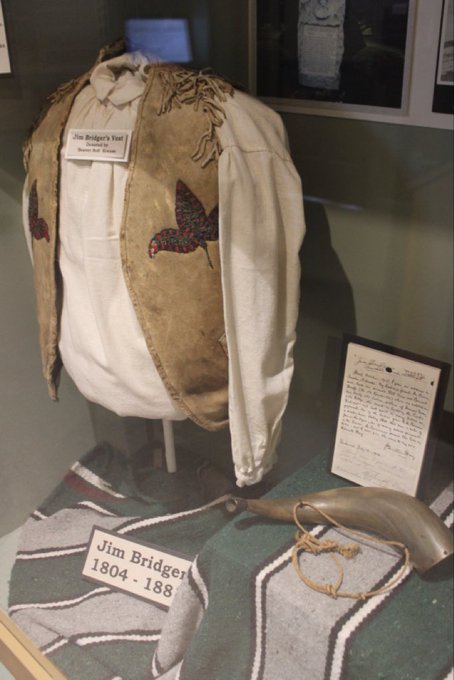

Fort Bridger was founded in 1842 by the famed mountain man, trapper, and scout Jim Bridger as a fur trading post. His initial fort, recreated here, was quite modest.

Mountain man Jim Bridger’s vest and powder horn, on display at Fort Bridger, Wyoming.

After a book published in 1845 strongly recommended that migrants to Oregon stop at Fort Bridger, a number of frontier businessmen turned it into a thriving depot for supplies and repairs.

Blacksmith demonstrating a forge at Fort Bridger, Wyoming. You can never use too many horse shoes and wagon tires!

General store (also called a sutlery) at Fort Bridger, for supplies past and present.

Starting in 1857, Bridger leased his fort to the US Army, which used it as the main staging base for President Buchanan’s military campaign to impose Federal authority over the Mormons in Utah.

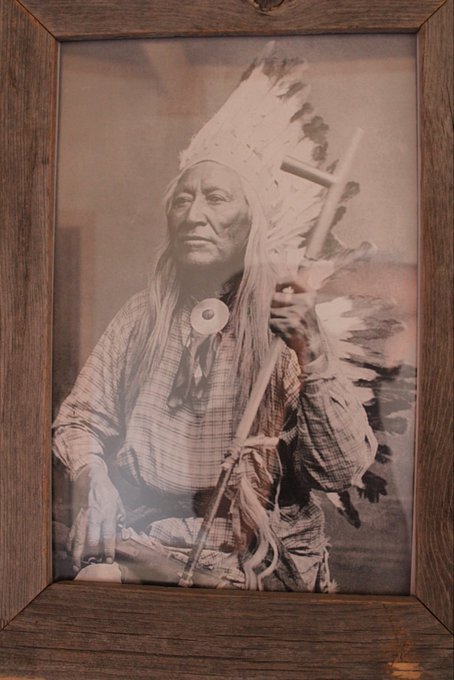

Both Bridger and the Army had good relations with the local Shoshone tribe, particularly Chief Washakie. In fact, Bridger married one of the chief’s daughters.

Fort Bridger continued to operate as a military post until 1890, when it was abandoned.

Right next to Fort Bridger is another fascinating historical rest stop: one of the first motels in the United States.

The property was developed in order to accommodate drivers along the new Lincoln Highway, the first paved road running coast to coast.

Every cabin had its own garage.

The bed and table inside were spartan, but clean.

Jim Bridger outside, beckoning you to his RV Camp.

At Fort Bridger, the trails split. The Oregon Trail turned north towards the Bear and Snake Rivers, and the Mormon Trail continued west into Salt Lake City.

We are going to come back almost all the way to this point to follow the Oregon Trail. But first we followed the Mormon Trail – and the Pony Express, and the Transcontinental Railroad (which you can see here) – into Utah.

The Transcontinental Railroad traveling down through Echo Canyon, into Utah.

So why did the Mormons go to Utah? Well, back in Missouri I mentioned Liberty Jail, where their founding prophet, Joseph Smith Jr, had been imprisoned. Tension and trouble followed them to their new home in Illinois, where Smith was killed by a mob.

Tensions were driven by 3 main things: 1) resentment of Smith’s claim to have received a new revelation, complementing the Bible, 2) the Mormons’ close-knit, communal way of life, and 3) Smith’s later adoption of the practice of plural marriage, or polygamy.

After Smith’s murder in 1844, the new leader, Brigham Young, decided to leave the United States to settle in a “new Zion” in the Salt Lake valley. Ownership, at that time, was unclear between Mexico and the US. That and distance would give the Mormons a great deal of autonomy.

I’m not going to get deep into the theology here. I’m just going to enjoy these Mormon Funeral Potatoes and this chicken pot pie.

We got them at “The Garage on Beck”, outside a oil refinery north of downtown Salt Lake City. I didn’t realize it was a bar, and couldn’t serve anyone under 21, but they kindly let us eat outside.

In any case, in July 1847, Brigham Young arrived in Emigrant Valley (behind the monument) with an advance party of migrants and supposedly said “This is the right place” and that was that.

Prior to leaving for Utah, Young urged his followers to form a “Mormon Battalion” to fight in the Mexican-American War, proving their loyalty to the US. They did, but suspicions back East remained.

We received a very warm welcome in Salt Lake City’s Temple Square from young volunteers who were generous in explaining their faith and their heritage to us. Many of them had had their planned missions overseas cancelled because of COVID.

We began our tour in the Assembly Hall, built in 1877, which at least looks like a traditional gothic church.

Then we moved next door to the Salt Lake Tabernacle, an auditorium-like building built from 1863 to 1875 to house larger-scale meetings of several thousand people.

The volunteers demonstrated the amazing acoustics inside the hall by speaking from the pulpit without a microphone. We could hear them clearly.

The Salt Lake Tabernacle is home to the famous Mormon Tabernacle Choir, who weren’t performing due to COVID. Twelve US Presidents, starting with Theodore Roosevelt, have spoken from the Tabernacle pulpit.

At the center of the complex is the Salt Lake Temple, undergoing a significant renovation. It is home to special sacramental ceremonies that take place in the life of Mormon believers.

Nearby is a huge office building for the Church. My son wondered why the Pope doesn’t have one of these at the Vatican.

Nearby is Brigham Young’s house, The Beehive.

Bees (seen here on the door knob of Brigham Young’s house) were seen as a metaphor for the collective spirit of industry and social justice he wished to instill among Mormons in their new Zion.

Initially, Young wanted every Mormon to commit all of their property to the Church. Meeting resistance, he recalibrated this to tithing a share of their income to support church charities, such as this common grain silo at Welfare Square.

Brigham Young tried to organize the economy of Deseret (the Mormon name for their Utah dominion, meaning “beehive”) in the form of collective co-ops, some of which continue to operate today.

Brigham Young’s desk in his home, The Beehive, where he worked as territorial Governor, until President Buchanan forced him to relinquish this role, under the threat of a military invasion.

Brigham Young was originally a carpenter by trade. Some of the tools in this chest, labeled BY, are originals belonging to him.

Brigham Young was “sealed” to 56 wives, though it’s hard to figure how he had the time to interact with them all. At least 12 of them lived next door in the Lion House.

Brigham Young used to take naps on this couch. I don’t blame him.

The family, including the many employees he took on to manage his estate, was so large that Young operated a small store out of the back of The Beehive. Each wife had an account at the store.

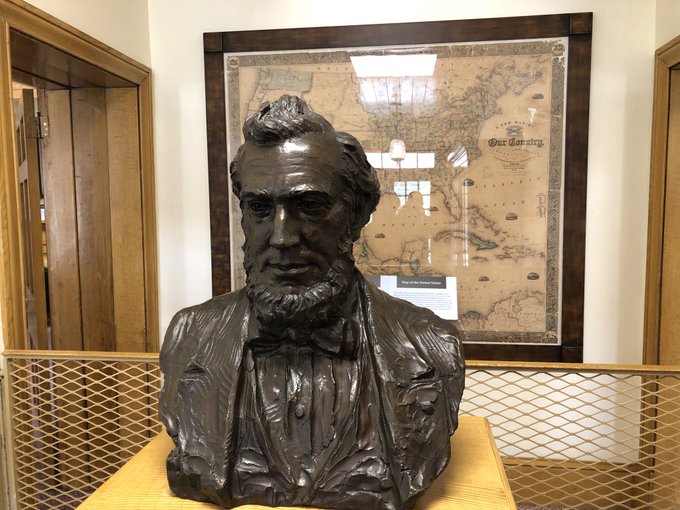

During the Civil War, Lincoln pretty much let Brigham Young and the Mormons to their own affairs, not wanting to stir up another hornets nest he didn’t need. But in the late 19th Century, the federal government started cracking down severely on polygamy.

As a result, Church leaders decided to urge all Mormons to comply with the law and practice monogamy. Soon afterwards, in 1896, Utah was admitted as the 45th state.

One interesting thing is that the Mormon belief in baptizing ancestors by proxy (to bring them into union with Christ) has led them to compile extensive worldwide genealogical records. This makes their library a prime resource for anyone researching their own family tree.

The Tabernacle is now too small to hold Church-wide meetings, and has been augmented by a huge conference center across the street.

By now we were about all Mormon-ed out, so we headed to Iceberg Drive Inn (supposedly a Salt Lake City institution) for a thick shake.

These are supposed to be the “mini” shakes.

The next morning we traveled north to Antelope Island State Park, on an island in the Great Salt Lake, known for its herds of bison.

The Great Salt Lake, the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere, is known as America’s Dead Sea. It’s salinity varies from 5% to 27%, compared to 3.5% for sea water and 33.7% for the Dead Sea between Israel and Jordan.

Of course if you swim in it you’re supposed to float, but despite being August, it was WAY too cold that day (in the low 50s) to even think about braving the swarms of brine flies and brine shrimp we’d been warned about to take a dip.

It really didn’t take too long at all to find the bison on Antelope Island.

The bison herd was introduced there in 1893, and now numbers between 500 and 750 animals.

Bison sitting beside the Great Salt Lake, Antelope Island, Utah.

Whenever people see this and get worried I got too close to the bison (which can be dangerous), my son laughs, knowing I was sitting safely in our car with a large telephoto lens.

After Antelope Island, we continue north of the Great Salt Lake to Promontory Summit, where we were just in time to see the arrival of the replica Union Pacific #119 locomotive.

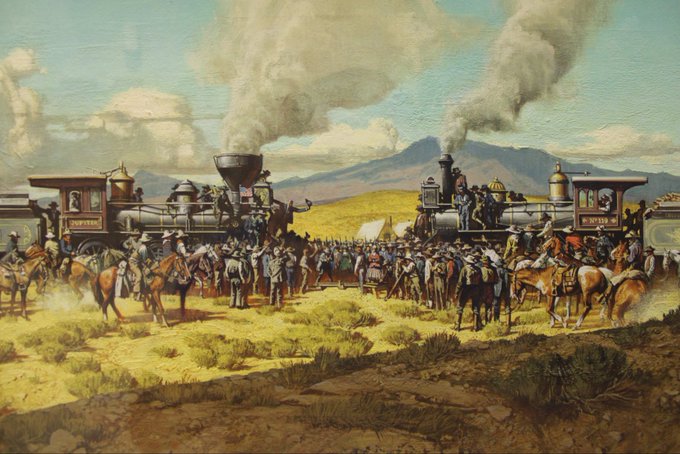

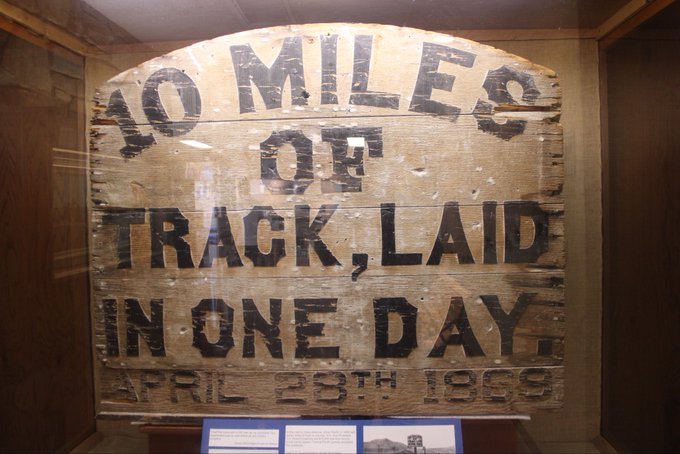

Promontory Summit is where, on May 10, 1869, the Central Pacific (from the west) and Union Pacific (from the east) met, and with a golden spike to unite them, completed the first Transcontinental Railroad across the US.

The Central Pacific was built from California using mainly imported Chinese labor, while the Union Pacific, which started in Omaha, relied mainly on Civil War veterans and Irish immigrants.

Because they were being rewarded per mile built, both railroads were in a race to see where they would meet – which ended up being smack in the middle of nowhere.

Why didn’t they meet in Salt Lake City? Because Brigham Young, fearful of the persecution the Mormons had faced back East, wanted the transcontinental railroad as far as possible from his new Promised Land. At least initially.

Unfortunately we arrived on a day when the Central Pacific locomotive, the #60 “Jupiter”, was in the shop for the regular maintenance. But it was still cool to see one of them chugging along under steam.

The Union Pacific #119 in operation at Promontory Summit, Utah.

From Promontory Summit, we drove back all the way past Ogden, back up Echo Canyon, and on to rejoin the Oregon Trail in Wyoming – watching out for antelope, of course.